VuwCTF 2025 string-inspector: Obfuscating control flow using execve syscalls

VuwCTF 2025 - string-inspector

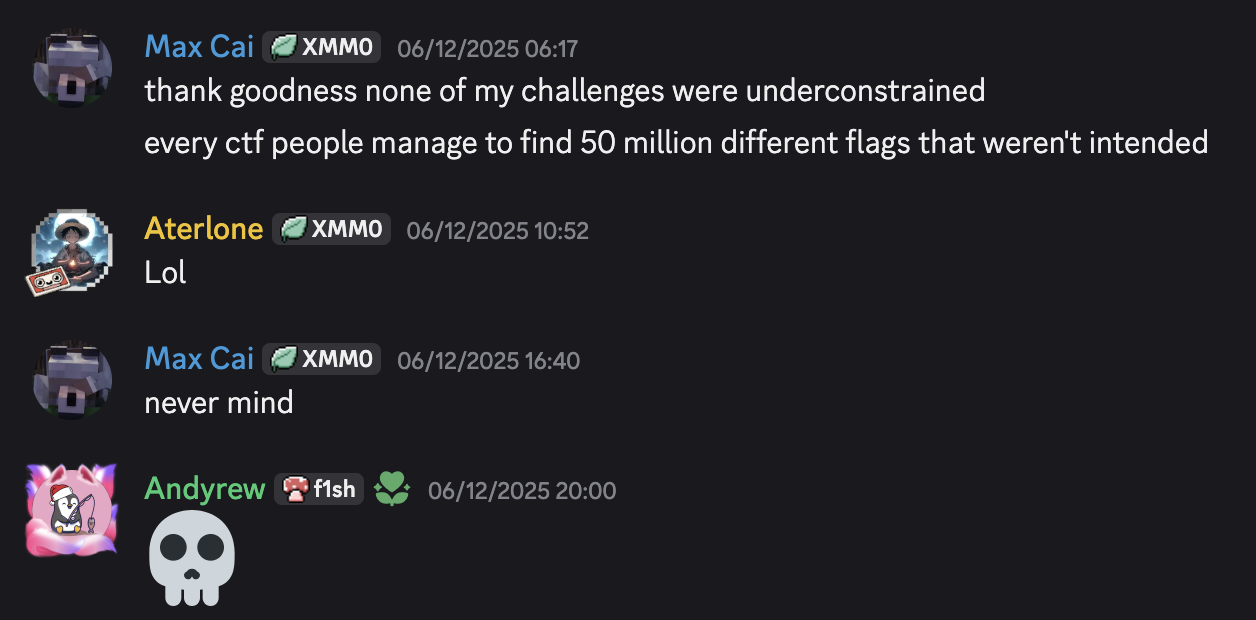

Of course one of my challenges had to be underconstrained.

string-inspector actually wasn’t the hardest rev challenge I made for

VuwCTF’s hybrid CTF competition, but had by far

the funniest unexpected outcome.

In this author writeup, I will talk about the design of the program and

some of the cursed things that caused this challenge to behave unexpectedly.

The Program

From some surface-level analysis, we can see that the binary expects a flag with 13 digits inside. Putting this through strace, we see some pretty weird behavior:

> strace ./inspector VuwCTF{9999999999999} 2>&1 | grep execve

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "VuwCTF{9999999999999}"], 0x7ffc92c7ddf8 /* 29 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "9999999999999", "0000000"], 0x7ffe3d3d6488 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "1532699999999", "0000000"], 0x7ffe22de7878 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0685969999999", "0000000"], 0x7ffcd1c3a4f8 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0601296999999", "1000000"], 0x7ffe21d83f68 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0516623999999", "2000000"], 0x7ffc3b2ce358 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0431950999999", "3000000"], 0x7ffcd8997108 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0347277999999", "4000000"], 0x7ffcb7c21718 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0262604999999", "5000000"], 0x7fff438d0c28 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0177931999999", "6000000"], 0x7ffca67cc3b8 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0093258999999", "7000000"], 0x7ffecccc8778 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0008585999999", "8000000"], 0x7fff3678c778 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0000118699999", "8100000"], 0x7fffce943ee8 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0000034026999", "8101000"], 0x7ffc5cf96d58 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0000025559699", "8101100"], 0x7fffae6f9f78 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0000017092399", "8101200"], 0x7ffea9265b78 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0000008625099", "8101300"], 0x7ffc03331d08 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0000000157799", "8101400"], 0x7ffd8c38f968 /* 0 vars */) = 0

execve("./inspector", ["./inspector", "0000000073126", "8101401"], 0x7ffc19d45b18 /* 0 vars */) = 0

This is pretty weird! The program seems to be doing some form of recursive iteration by calling itself, each time slightly modifying the inputs until the code converges on a result. Each pass, the program seems to only do some basic string algorithms on the numbers- it doesn’t even decode the entire string into a binary number to perform ALU operations. The one-argument invocation with the flag is simply an entrypoint into this bizzare, recursive calculation.

The Algorithm

The code has three basic string algorithms which process our ascii decimal char strings. This is the first function I implemented, with the comments removed:

int can_subtract_from(const char *source, size_t source_offset, const char *minuend) {

if (strlen(source) - source_offset < strlen(minuend)) {

return 0;

}

for (size_t i = 0; i < source_offset; i++) {

if (source[i] != '0') {

return 1;

}

}

for (size_t i = 0; i < strlen(minuend); i++) {

if (source[source_offset + i] < minuend[i]) {

return 0;

}

if (source[source_offset + i] > minuend[i]) {

return 1;

}

}

return 1;

}

This code does an in-place comparison on two big-endian decimal strings

to check whether a minuend can be safely subtracted from a source string.

For example, 20000 - 12345 is allowed, but 9999 - 12345 isn’t.

This comparison requires the source to be at least as long as the minuend,

and for each significant digit to be no less than that of the minuend.

With compiler optimisations enabled, this algorithm would translate to

a O(n) traversal of the strings.

The next string algorithm is responsible for actually performing that subtraction operation, borrowing digits if necessary. Due to the nature of the encoding format, this code required a nested loop.

void subtract_from(char *source, const char *minuend) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < strlen(minuend); i++) {

if (source[i] < minuend[i]) {

size_t borrow_idx = i - 1;

while (source[borrow_idx] == '0') {

source[borrow_idx] = '9';

borrow_idx--;

}

source[borrow_idx] -= 1;

source[i] += 10;

}

source[i] -= (minuend[i] - '0');

}

}

The final algorithm is the simplest of them all: it increments a number, carrying any nines to the left.

void increment_digit(char *number, size_t idx) {

while (number[idx] == '9') {

number[idx] = '0';

idx--;

}

number[idx] += 1;

}

The Recursion

The main code simply uses these functions to search for a place to subtract a divisor to get the result. After the operation, it will perform a recursive execve call, conveniently restarting the algorithm to avoid any problems.

size_t dividend_len = strlen(dividend);

size_t divisor_len = strlen(divisor);

size_t quotient_len = strlen(quotient);

for (size_t division_idx = 0; division_idx < dividend_len; division_idx++) {

if (can_subtract_from(dividend, division_idx, divisor)) {

subtract_from(dividend + division_idx, divisor);

increment_digit(quotient, quotient_len - dividend_len + division_idx + divisor_len - 1);

char *new_argv[] = {

argv[0],

dividend,

quotient,

NULL

};

char *new_environ[] = { NULL };

execve(argv[0], new_argv, new_environ);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

}

The recursive execve syscall will effectively reset the computation with the changed parameters,

meaning that the end of the loop is only ever reached if the code finds no place to subtract,

signalling that the computation is done.

Putting all this together, we can see that this code emulates an inefficient long division algorithm

using only subtraction and iteration. After subtracting out all multiples of the dividend 84673,

the code performs a simple constraint check, requiring the quotient to be equal to 0319993 and

the remainder to be equal to 0000000000042.

One would expect that this arithmetic equation can only have one correct solution.

The Mistake

Each time this long division algorithm performs a subtraction, it needs to increment the count at the appropriate place. In the main function, the code runs this code:

increment_digit(quotient, quotient_len - dividend_len + division_idx + divisor_len - 1);

Note: this took me a solid ten minutes to think through and make sure there weren’t any off-by-one errors. I never want to work with reverse-order decimal arithmetic ever again.

As it turns out, if the quotient is too small, this code can actually compute a negative index to increment to,

making an out-of-bounds access and corrupting any data around this heap segment! This undefined behavior

didn’t cause the program to crash because the execve syscall reïnitializes a fresh copy of the runtime,

completely ignoring the corrupted heap metadata. Perhaps execve is the future of memory safety.

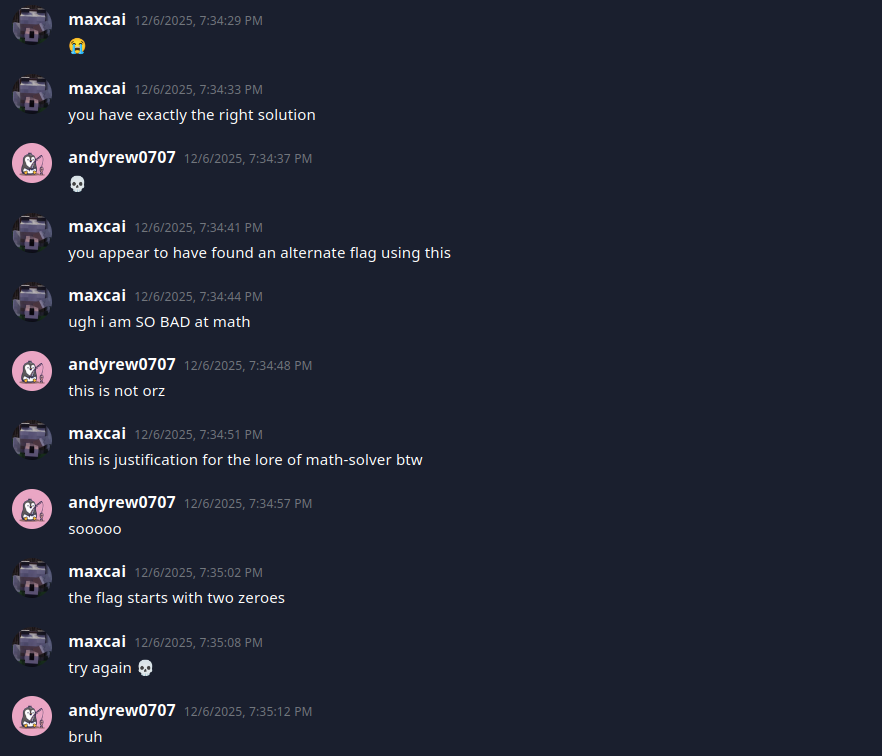

Andyrew from team tjcsc found two

alternative solutions that passed the flag verifier due to this underflow, realizing that the quotient

didn’t have to mathematically equal to 319993, as long as the result was the same in the process (mod 10^7).

This means that the program accepted the flags 0873824767331 and 1720554767331, despite invoking

out-of-bounds access and corrupting the glibc heap.

I genuinely did not see this coming, and didn’t even realize this bug existed in the challenge until Andrew opened a ticket reporting the problem. I’m genuinely impressed that players not only understood the program enough to solve the challenge, but also to find limitations in its logic.

Hats off to you, Andrew! Though next time, maybe try all your possible solutions, and immediately file a report when you find a discrepancy :^)

The correct input value was 84673 * 319993 + 42, zero-extended to take up

all thirteen digits, making the intended flag VuwCTF{0027094767331}.

The Conclusion

Unix has plenty of interesting syscalls which allow programs to do

bizzare actions that span beyond the scope of one singular runtime.

Through the use of the execve syscall, we can obfuscate control

and data flow, making both static and dynamic analysis harder.

In the string-inspector challenge, the code performs very simple

string looping algorithms and uses this recursion primitive to emulate

a more complex long division computation.

I tried to keep the code as simple as possible and omitted several bounds checks in my program, assuming that it wouldn’t harm the overall integrity of my reverse engineering challenge. However, I was wrong. One buffer underflow bug ended up introducing several unintended solutions to my challenge, causing some players frustration. In the future, I will make sure to be extra careful that my code is written correctly, just in case someone tries to pwn my rev challenge.